home: Jazz Chords for Baritone Ukulele

Seventh chords are the soul of jazz, and the baritone ukulele tuning is ideal for playing them—four notes, four strings, tuned for perfect four-part harmony.

X7 – Sevenths

There are a number of different sevenths chords. The most common, and the one referred to as a 7th chord, adds, not the 7, but the b7 to a major chord.

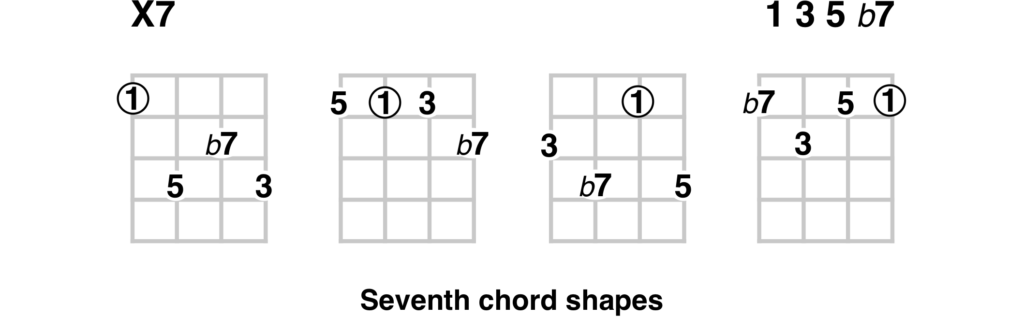

1 3 5 b7

These chords are generically named X7. For example, C7 has:

C E G Bb

D7 has:

D F# A C

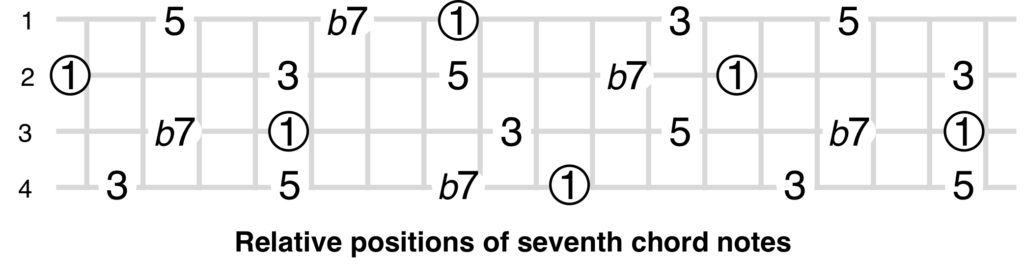

Here’s how the notes for building 7th chords lay out on the fretboard.

It would be nice if four chord shapes could be found, each one having its root on a different string.

It turns out that’s easy.

What a powerful tool this is! It means that, when trying to come up with an accompaniment for a song, and you need, say, a D7, you can make one rooted at any D on the fretboard.

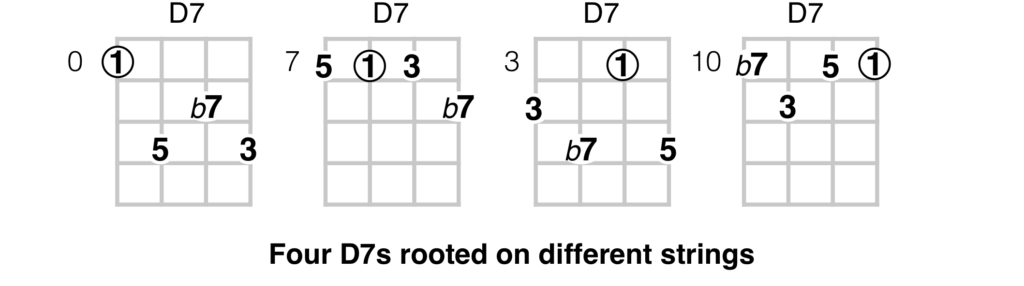

Here are the four ways to play a D7.

When playing accompaniments, sometimes chords sound better when played in the same area of the fretboard. So where might you like your D7? Near the nut? Way up at the tenth fret? Somewhere in the middle? You’ve got choices.

They give you variety in position on the fretboard, and in voicing. The chords with the root on one of the two lower strings sound different from the ones with the root on the higher strings.

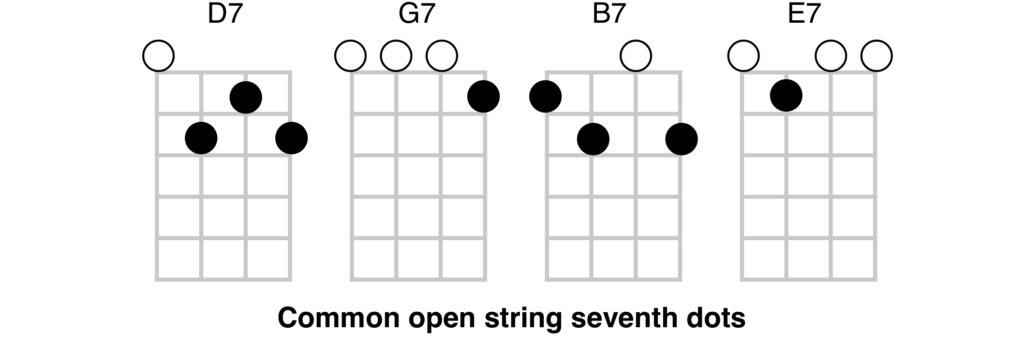

Note that each one of these shapes has a corresponding standard open string shape corresponding to the tuning of that open string. (Remember the strings are tuned to D G B E.)

Knowing the voices lets us realize that these are the chords where the root is the open string. So, for the G7 the open G string is the root. This can help you remember which string has the root for each movable shape.

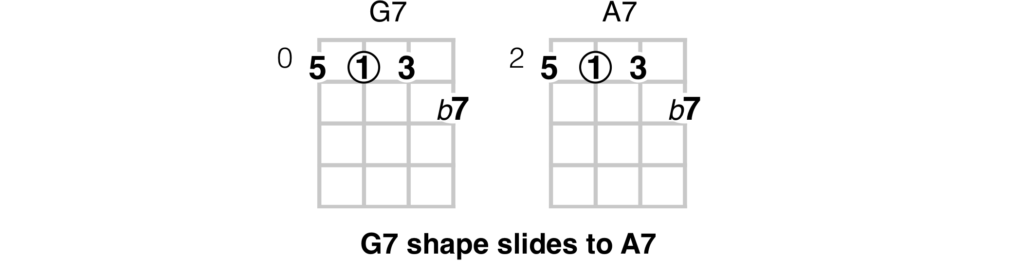

Slide that open G7 shape up two frets and the root is on the A of the third string, and thus an A7.

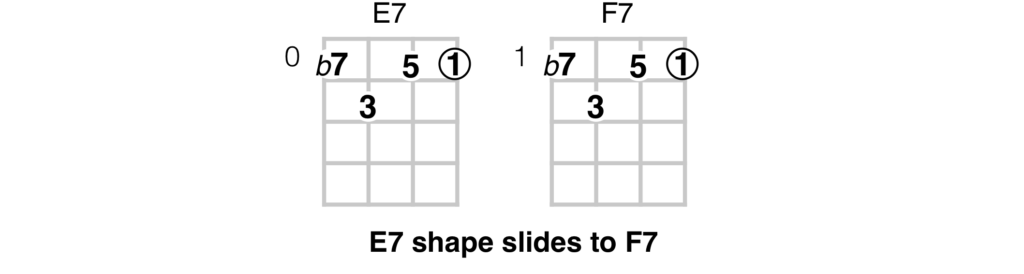

Similarly an E7 can be slid one fret to make a F7.

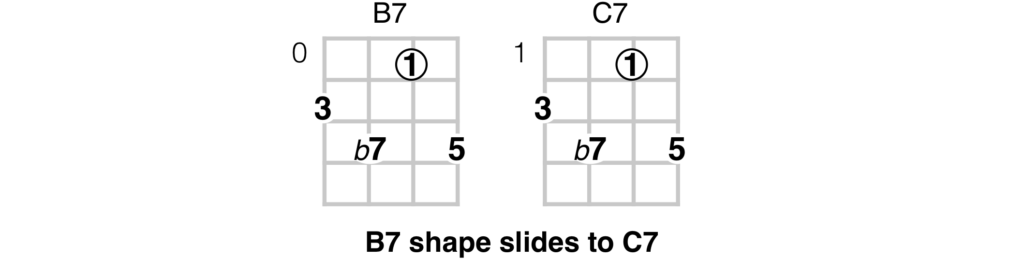

And a B7 to a C7.

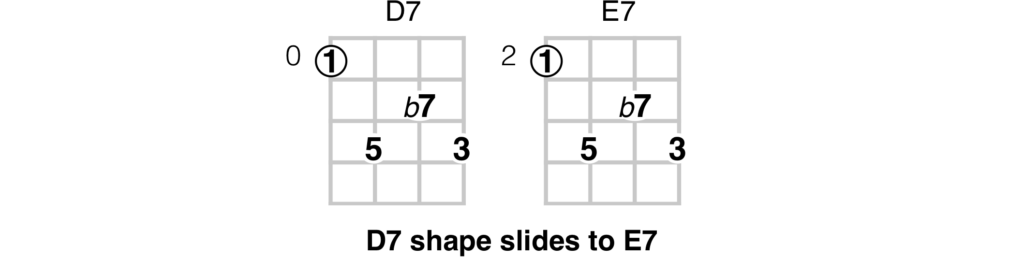

While we’re playing with the basic shapes, do we really like that E7 with its root on the highest string? Might it sound better if we had the root on the lowest string? We can get it by sliding the D7 up two frets.

See, or rather hear, the difference. Depending on the chords around it in a progression, one will sound better than the other.

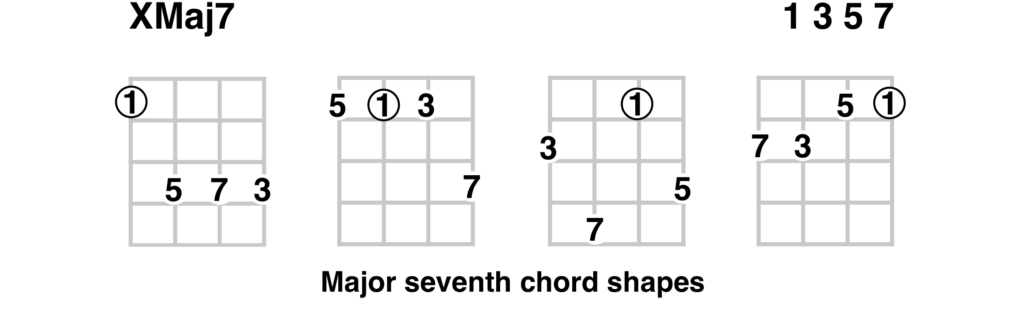

Major 7th Chords

Major 7th chords use the actual 7 rather than the b7 in the chord. To find the major 7th chords we could repeat the process above, showing where those notes are on the fretboard and looking for shapes that work. But there’s an easier way.

We can simply modify the X7 shapes to make them XMaj7 shapes. Knowing where the b7 is in a 7th chord, we can just take each X7 shape and move the b7 up one fret to a 7.

Doing that yields:

Compare this to the X7 patterns. If you understand this relationship, you don’t really need to memorize the XMaj7 fingerings as they can all be derived from the X7 ones by simply moving the b7 up a fret.

Experiment with these shapes and compare the sounds to those of the 7th chords.

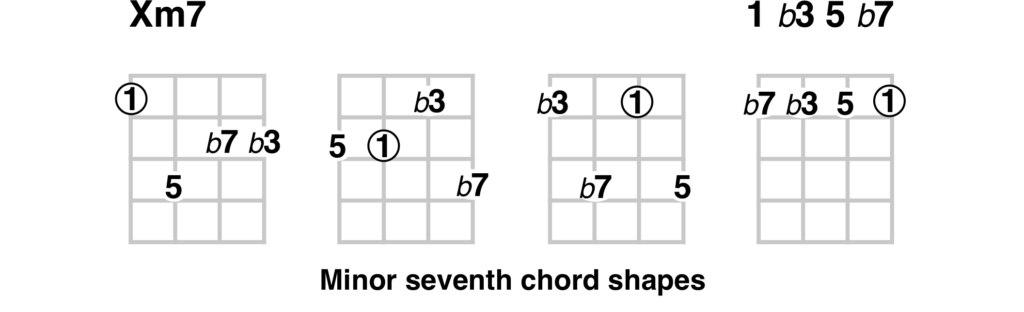

Minor 7th Chords

A minor 7th chord is the same a regular 7th chord, but with a flatted 3rd instead of a 3. I know what you’re thinking. We can take the shapes for the 7th chord and simply flat the 3s to come up with the four shapes for minor 7th chords. Exactly.

Once you know the shapes for the four 7th chords, you can easily figure out the minor 7th ones on the fly by flatting the 3s.

Note that the terminology is confusing for these chords. The “major” in Major 7th refers to the major 7th interval from 1 to 7. The “minor” in minor 7th refers to the first three notes being a minor chord.

Play with these up and down the fretboard along with the others. There are a lot of nice sounds here.

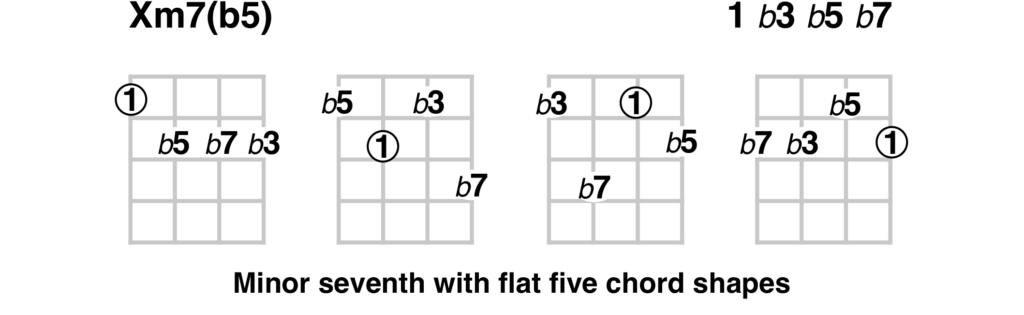

Minor 7th chords with b5

The name of this chord, Xm7(b5), is very descriptive. It is just like a minor seventh chord, but with a flatted 5, and can be easily derived by making that change to the Xm7 shapes.

This chord’s name makes it sound like a lot of the fancier, far-out, jazz chords. Many of those are non-essential variations for creating different moods.

But this one isn’t like those others. It plays a critical role in the suite of sevenths chords used in chord scales and progressions. We’ll see more about that soon.

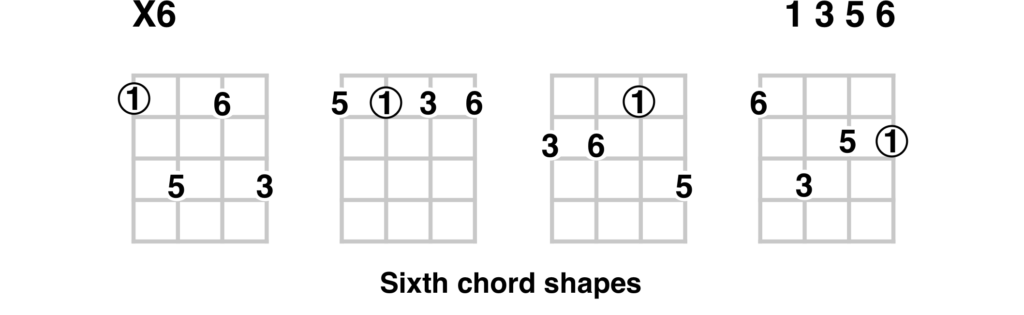

6th Chords

There are more 7th chords, but they are used more for spice than substance. We’ll cover them later. There is a 6th chord, however, that really belongs with these essential 7th chords.

A 6th chord has a

1 3 5 6

Its shapes can be easily derived from the 7th chords by moving the b7 back one fret to the 6. Like so:

But wait, did you notice something? These are the same fingerings as for the Xm7 chords, except the voices under the fingers have changed. For example, the b3 of the Xm7 is the (1) of an X6.

This situation is called a chord homonym, two different chords that are fingered the same, sharing the same notes but in different roles.

Is this a problem? Strangely it’s not. Each chord will sound correct for the context in which it is used. The voices moving from one chord to the next set expectations for the ear.

This will be illustrated in some of the progressions to follow.

Transformations

Here’s a summary of the transformations we’ve used so far to get the most important sevenths chords. Everything else will be just fluff.

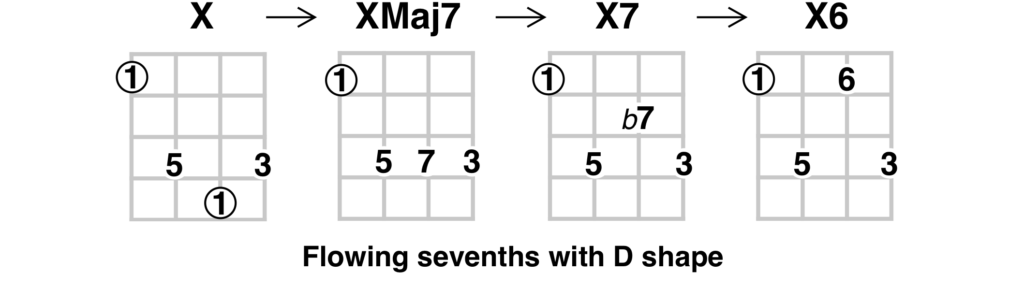

D and G shapes (1) 7 7b 6

You can get a nice sense of how these chords go together by playing them in sequence. Especially for those XMaj7 shapes that differ from a major (X) shape by having a duplicate (1) moved to a 7.

For those shapes you can start with the major chord and then keep moving the fingering on one string, creating this sequence:

(1) —> 7 —> b7 —> 6

Here it is for the major chord D shape.

It can be played anywhere. Playing it using the open string D gives the progression:

D —> DMaj7 —> D7 —> D6

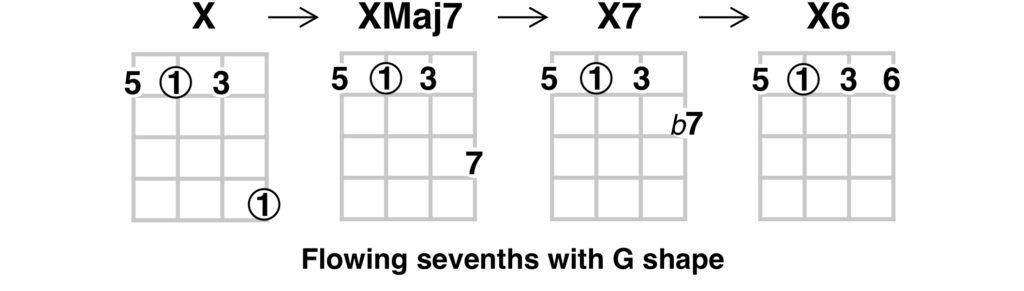

You can do the same thing with major G shape.

It can be used anywhere on the fretboard. Playing it using the open G is fun because it requires just one finger to play this progression:

G —> GMaj7 —> G7 —> G6

Note that when you get to the G6 playing in this progression it sounds like G6, not its homonym Em7. This is because the ear has just heard the same 5 (1) 3 voicing three times and expects it again.

C and E shapes (1) 7 7b 6

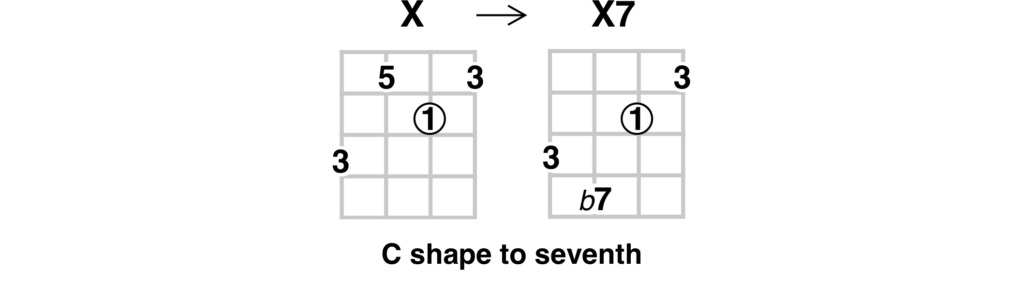

Trying to do a similar thing, playing the (1) – Maj7 – 7 – 6 progression starting from the other major chord shapes, the A, C or E, illustrates some of the compromises necessary in making chord progressions. None of these morphs nicely into the chord progressions above.

The problem with the major C and A shapes is they only have one (1). They don’t have a spare to drop one fret to make a 7.

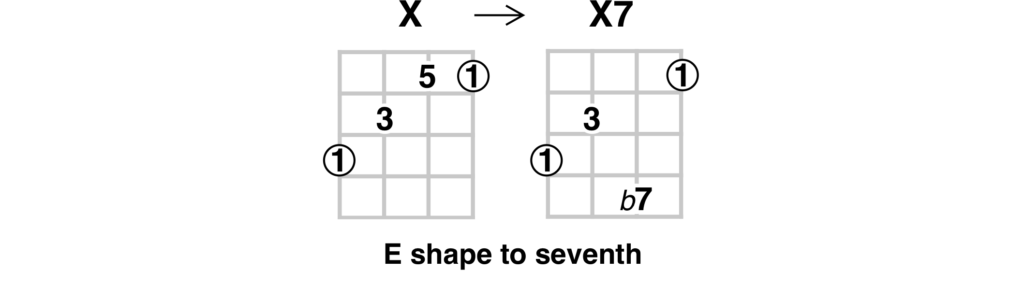

The E shape, on the other hand, has an extra, and there is no problem unless you try to play it using an open E chord. You run out of frets trying to drop down to the final 6.

However it you want to play the progression for A, C or E, it’s easy using the movable shapes. The progression can be played:

- in A by playing the G shape at the second fret,

- in C by playing the G shape at the fifth fret, and

- in E by playing the D shape at the third fret.

- Yay movable chords!

In fact, since the D and G shapes are about a half a scale apart, they can be used to play that descending sequence in any key without having to move above the fifth fret.

Other Solutions

There are other ways to make a C7 and an E7 using open strings. Both require losing the 5 and replacing it with a 7b.

Here’s how to morph the E shape to E7, moving the 5 up to b7.

Here’s how to morph the C shape to C7, again by moving the 5 to a 7b.

Because both of these compromises make for pleasing 7th chords, and both are fun to play by dropping a pinky down after playing the major chord, they teach an important lesson.

It is not always necessary to get all the notes in the right places. And, as we’ll see when we start adding additional notes to chords, the 5 (sorry 5) is often expendable.