Home: Jazz Chords for Baritione Ukulele

Here’s the Preface and Introduction from the book.

Preface

I played some guitar and wanted to accompany my girlfriend on the jazz songs she liked to sing. Like Rodgers and Hart’s Bewitched Bothered and Bewildered.

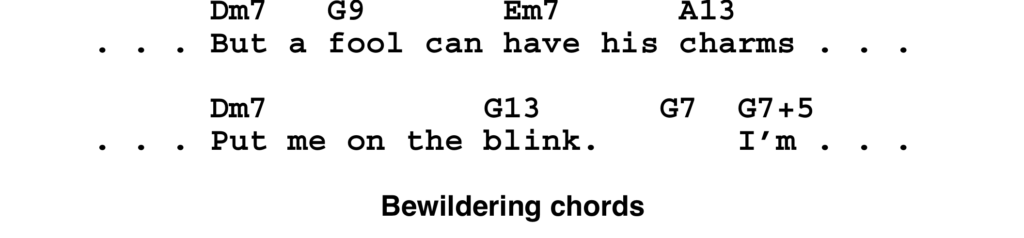

But I quickly ran into chords I’d never seen before, like these:

I was OK with the 7th chords, but G9? A13? G7+5?

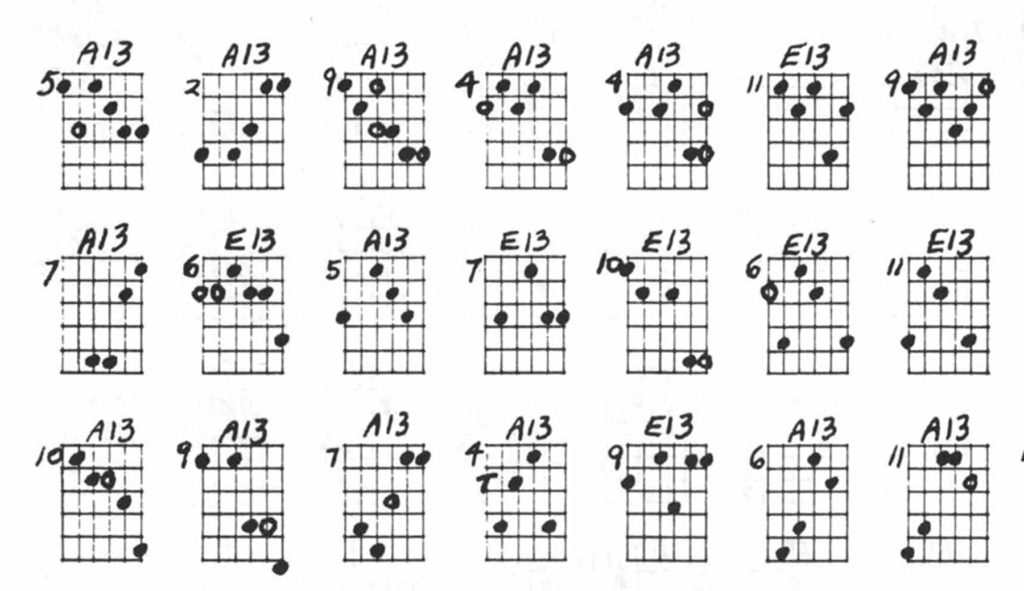

Looking them up generally led to one of two equally unsatisfying results. Either a single diagram was displayed that just didn’t sound right in the song I was trying to play, or I was presented with an overwhelming array of possibilities.

Here, for example, are 13 ways to play an A13 chord on a guitar, from Ted Greene’s encyclopedic Chord Chemistry.

Curiously, the single recommended fingering of an A13 that came with my version of Bewitched Bothered and Bewildered apparently wasn’t good enough to make this list.

I wanted to learn more about how these chords were derived, I wanted to know which of the dots made a chord an A, which made it a 13, and which dots made the G7 to G7+5 so full of anticipation.

I started to delve into these issues on my guitar, making notes, drawing the sorts of diagrams that appear throughout this book, but still, six strings, so many ways to play the four note chords, some fingerings difficult to play.

Maybe there’s a simpler way to learn about jazz chords. A way with fewer strings to deal with, yet one that aligns perfectly with the four part harmonies of the chords. A way that’s easier to play and still captures the subtle sounds and beauty of those chords…

I had a baritone ukulele.

Introduction

“Everything should be made as simple as possible, but not simpler.” — Albert Einstein

In case you missed the cover, here’s how a guitar, baritone ukulele and soprano ukulele compare in size. The baritone has the simplicity of four strings, but with a larger body than the soprano. That makes it sound more like a small guitar than a big ukulele.

But it doesn’t matter which you use with this book. That’s because it’s all about movable chord shapes and the jazz voices they play.

The four strings of the baritone ukulele are tuned the same as the four high strings of the guitar, so everything in this book can be played on a guitar. Further, the ideas in the book can be easily extended to the full guitar, adding complexity of course.

As to the soprano ukulele, it is tuned differently from the baritone ukulele but the relative spacing of the strings is the same. This means that any chord shape in this book can be played on the soprano ukulele as well, it will just be at a different pitch. For example, the shape and fret used to play a G7 on the baritone ukulele will play a C7 on the soprano.

Four Note Chords

Almost all jazz chords for guitar are defined by four notes. You might say there are lots of five and six string guitar chords. Yes, but they usually only have three or four unique notes. The rest are duplicates. For example, the classic six string E chord has three Es in it.

For lots of jazz chords, and in particular all the seventh chords, which are the foundation of jazz, there are only four notes in the chord. Three for the base chord and one for the seventh. As you read on you’ll see that the ukulele tuning is ideal for playing these. It’s almost as if it were designed for that purpose.

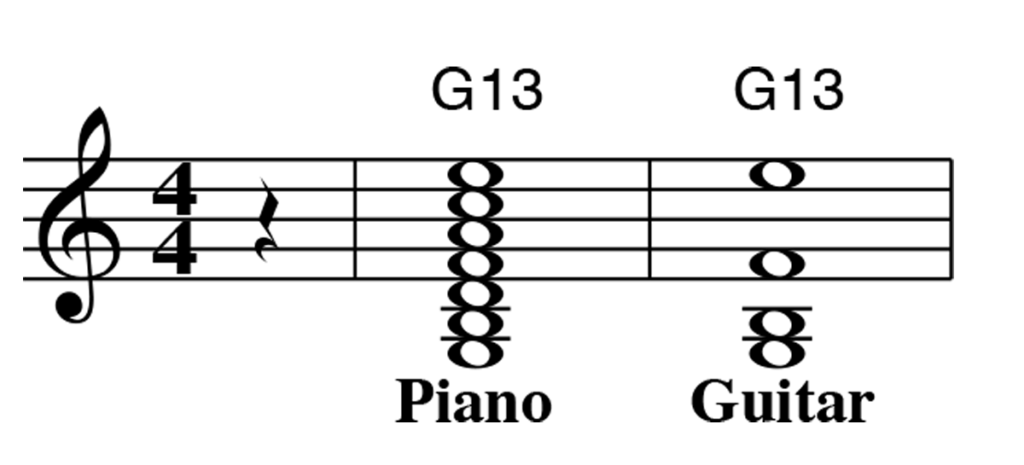

The higher, more complex chords have additional notes. The biggest is the thirteenth chord with seven notes in it. It can be played on a piano, but for guitar, only the notes that give it its distinctive sound are used.

So for whatever chord, four notes covers it.

Hidden Voices Beneath the Dots

There are two factors that go into any chord diagram: fingering and voicing.

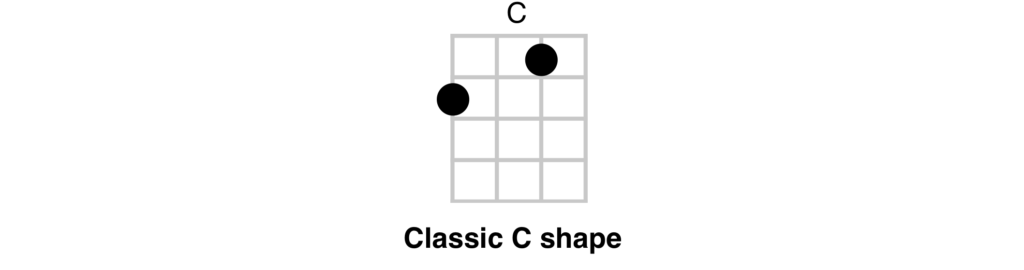

Fingering tells you where to place your fingers to make a chord. Here’s the chord diagram for the classic C chord.

It gives the fingering. The how of playing a chord.

Voicing tells you the notes that go into a chord and the order in which they’re played. That classic C chord has, starting from the low fourth string, these notes in this order.

E G C E

Those are the voices of the chord. The why of the chord.

The voices are hidden in the classic dot diagrams.

For the basic chords, this isn’t a problem. It’s just fine to memorize the few shapes needed to accompany most regular songs. When the music says strum a C, well then, strum a C. It’s not necessary to understand the why of a particular voicing of chord, just how to play it.

But for jazz, it’s all about the voices.

- You can learn to play a G13, but what makes it a 13th chord? What gives it its special flavor? And how does it relate to a 7th chord?

- You can learn to play a G7 and a G7+5, but what is it that creates that anticipation? How do they work together?

- And does one have to start all over for an A13? Or is there some overlap, and if so where?

The answers to all these questions are in the hidden voices.

The How and Why of Chords

This book is all about understanding both the how and why of chords. The more you understand the why, the less you’ll need to refer to chord charts for the how.

To this end, normal chord diagrams are used, except the dots are replaced with numbers. Each number indicates the relative note number being played on each string, a (1) for the root, 3 for the 3rd, etc.

This still tells you where to put your fingers, but also shows you the music, the harmonies, you hear when you play.

(Spoiler alert — the following example comes from near the end of the book, so it might not make perfect sense now but should give you a flavor of where the book is going.)

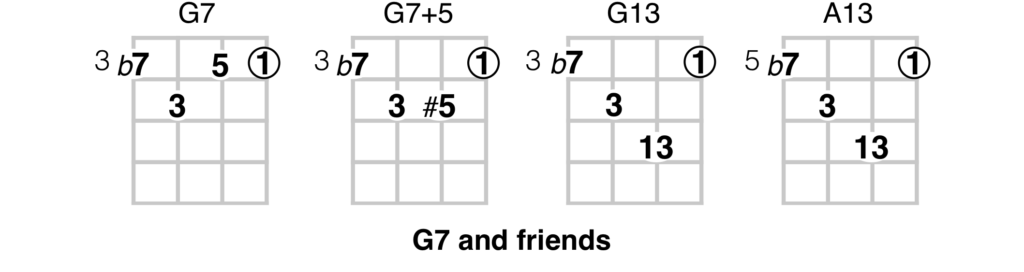

Here’s one shape for a G7 along with three other chords that are closely related. They all have the root on the first string.

The voicing for each shows exactly what the relationships are. In these four shapes we can see:

- The sense of anticipation you hear playing G7 to G7+5? It’s caused by moving the 5 up one fret, making it sharp. And it’s on the second string, so it’s easy to play by dropping a pinky on it after playing the G7.

- A G13? It turns out to be nothing more than a variation on a G7 with the 13 (that’s jazz talk for a 6) replacing the 5. Know one and you know the other.

- The A13? It’s included for free. Move the G13 shape so the root on the first string is over the A on the fifth fret.

And so on, each chord has a shape that shows how to play it and a voicing that tells its story. Knowing the stories let’s you understand the multitude of shapes available for jazz, and how best to link them together for that smooth jazz sound.

So let’s begin at the beginning with scales, the fretboard, and major chords.

Kindle edition $4.99 – Jazz Chords for Baritone Ukulele

Home: Jazz Chords for Baritione Ukulele